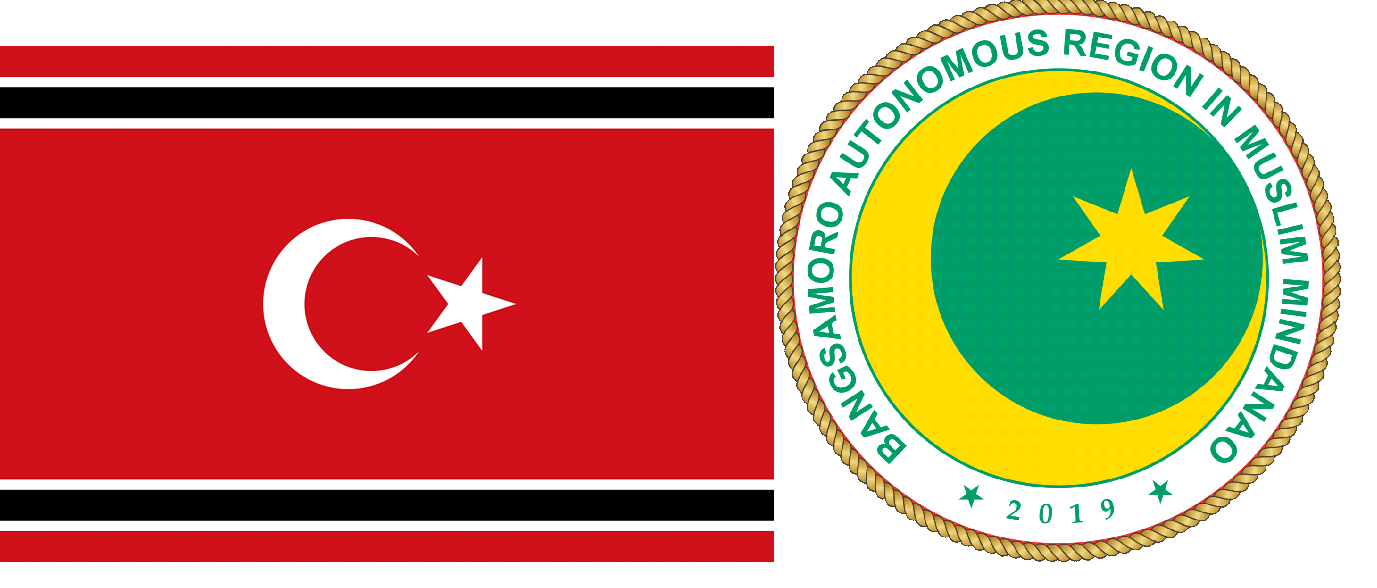

One of the most complex phenomena in post-colonial Southeast Asian history is the protracted conflict in Aceh and Bangsamoro. In Aceh, the conflict has been ongoing since the proclamation of the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM) in 1976. For nearly three decades, the GAM conflict was protracted due to various central government policies that were considered detrimental to Aceh, such as the unfair distribution of resources, neglect of identity, and a culture of complacency. This conflict ended in 2005 with the Helsinki Agreement. Bangsamoro, on the other hand, is the long struggle of the Moro Muslim community in the Philippines demanding the enforcement of autonomy and recognition of cultural and social autonomy. The granting of autonomy in 2018 was also marked by the ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law.

In both cases, the solution sought was not only to end the armed conflict, but also to integrate, sustainably, socially, culturally, and economically. If the settlement does not empower local communities, then a settlement that ignores symptom control has the potential to fail in the long term, leading to violence and instability. To that end, the greater understanding of special autonomy for Aceh and Bangsamoro is strong evidence that greater local sovereignty is one of the ways to build peace and development.

Special Autonomy: More than Decentralization

Special autonomy is form of asymmetric decentralization granted to specifically defined regions usually as a consequence of cultural, historical, or post-conflict political factors.

An entity with special autonomy status is not merely a delegation of administrative power, but also recognition of the social, cultural, and historical identity of a social unit that has long been recognized by the central government as a peripheral member. Special autonomy is designed to restore cultural and social power, placing power in the hands of local communities over socio-economic development and local resource management.

In Aceh, for example, the recognition of special autonomy has legitimized the enforcement of local customary law and Islamic law as characteristics of Acehnese identity. In the case of Bangsamoro, the recognition of special autonomy accommodates the diversity of ethnic and religious identities and provides a more inclusive government structure.

Thus, special autonomy not only captures the political integration of peripheral regions into the central government, but also functions as a means of sustainable decolonization. Unlike farmers who were born out of colonial conditions, marginalized and peripheral communities are empowered and empower themselves holistically.

Sustainable Decolonization: Dissecting the Social and Cultural Dimensions

Sustainable decolonization is a transformative multidimensional social and cultural process accompanied by political and economic impacts that are relevant to Aceh and Bangsamoro. In Aceh and every residual conflict in Bangsamoro, the impact is not only the void of infrastructure (physical and social) and the destruction of social networks and cultural identity.

The process of sustainable decolonization involves the revitalization of cultural identity accompanied by the reconstruction of colonial society and the recollectivization of plural social destruction. Social destruction is prone to exclusion, and social rehabilitation must be prepared to adapt in a sustainable manner.

In Aceh, as result of post-conflict, special autonomy is primarily for the preservation of customary law and Islamic law. Bangsamoro has diverse Islam, in addition to religious pluralism. With special autonomy, Aceh is a formal substitute for diplomacy and unique survivalism, despite the economic risks and dialectics of reins brutalization of conflict.

The experiences of Aceh and Bangsamoro: two paths, one goal

However, Aceh has shown how special autonomy can be a bridge for reconciliation and sustainable development, despite challenges such as corruption and socio-economic inequality. Aceh's experience in the process of development and peace over the last two decades is a valuable resource for other regions. Meanwhile, Bangsamoro is still in the process of institutional and political consolidation. Therefore, Aceh has become a focus of study for Bangsamoro in creating more effective autonomous government and more inclusive reconciliation.

Both regions show that, despite differences in their socio-political contexts, the goal of sustainable decolonization with special autonomy remains consistent. It is interesting to establish lasting peace, affirm local cultural identity, and inclusive socio-economic development. With this approach, it is hoped that the colonial legacy and conflicts within society can be transformed into development potential for a more harmonious and just society.

The Role of Local and International Institutions in Establishing Transformation in Aceh and Bangsamoro

The institutions established in Aceh have been an important inspiration in the management of special autonomy for Bangsamoro.

In Aceh, institutions such as the Aceh Representative Council, the Ulama Council, and the Wali Nasggroe institution have become guardians of pluralistic culture and politics, as well as facilitators of the reintegration of former GAM fighters into civil society. Local political parties, which are mostly filled by former combatants, also serve as important channels in the democratic mechanism and the participation of the Acehnese people in democracy, as quoted in keunikanaceh.com.

As for Bangsamoro, the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) passed in 2018 stipulates the formation of a government institution consisting of 80 members of Parliament and 15 Ministers. For governance, members of Parliament become Governors of each constituent part of Bangsamoro in accordance with Bangsamoro's inclusive government and power sharing in Article 31 and socio-political and socio-economic governance in Chapter 4, which includes a framework for peacebuilding with socio-economic intervention.

Unlike Aceh, the Bangsamoro government structure, which adopts lessons from Aceh, dynamically transfers governance and autonomy in resource control to local command. The role of international institutions such as the United Nations (UN) and donor organizations in providing the technical, financial, and dialogue support necessary to help both regions maintain peace and improve institutional frameworks is critical.

Synergy between local and international agencies helps in the process of social reconstruction while simultaneously reducing the likelihood of conflict recurrence.

Overcoming Obstacles and Optimizing Opportunities

Some of the challenges facing both regions are corruption, socio-economic disempowerment, and complex local political dynamics shaped by colonialism, conflict, and their legacy. Exploring the transcendence of accountability and transparency issues in the management of special autonomy funds is also very complex. Enhancing initiatives that emphasize community participation and bureaucratic reform are the most critical aspects for the success of special autonomy. Local staff development and greater efforts in control oversight will ensure that the benefits of development are widespread and equitable.

Conclusion and Reflection

Special autonomy is a very important component in the ongoing decolonization process in post-conflict Aceh and Bangsamoro.

Special autonomy not only includes providing a context for the recognition of cultural and local political sovereignty, but also the development of inclusive governance and community empowerment. Aceh and Bangsamoro show that the success of special autonomy is influenced by commitment to transparent management, community participation, and the support of international institutions.

In this regard, the author sees that all stakeholders still need to make adjustments within the existing framework of special autonomy through policy strengthening and cross-sectoral collaboration as an effort to achieve peace and social justice. Thus, Aceh and Bangsamoro deserve to be called examples of peaceful transition and models of sustainable and equitable post-conflict community development in the ASEAN region.

This article explores how special autonomy in Aceh and Bangsamoro...

This article examines how Malaysia’s political economy sustains social harmony...

This article critiques the Global Innovation Index (GII) for overlooking...

This article examines how technology has become a highly contested...

This article takes a deep dive into Indonesia’s evolving struggle...

This article examines how Nepal’s Generation Z transformed a government-imposed...

This article explores how religiosity in Indonesia, while rooted in...

This article explains Aceh's efforts to balance high expectations with...

This article examines Nigeria’s northern insecurity crisis as more than...

This article explores Indonesia’s potential to develop a sustainable national...

This article discusses the implications of the removal of Imran...

This article explores how digital fandom surrounding West Java Governor...

This article explores how climate change is reshaping global security,...

This article analyzes the fragile foundations of President Prabowo Subianto’s...

This article examines how democracy can paradoxically bolster authority held...

This article examines the ECOWAS Court’s ruling against Nigeria’s Kano...

This article explores the fearless activism of Mahrang Baloch, a...

This article examines the controversial approval of a presidential state...

This article examines Sudan’s turbulent path toward democracy, where military...

Pope Francis’ visit to Indonesia marked a significant moment for...

This article examines the underrepresentation of women in Nepal's labor...

The 2024 regional elections in West Sumatra marked a significant...

The article explores Syria’s prospects for a democratic transition following...

By examining overlapping identities and marginalization, especially in the Global...

Leave A Comment